Evaluating OCD Treatments: The Benefits of Specialized Care

- Ryan Burns

- May 14, 2025

- 25 min read

SCIENCEWORKS BEHAVIORAL HEALTHCARE

May 2025

Introduction

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD) is a complex mental health condition characterized by recurring, unwanted thoughts, images, or urges (obsessions) that trigger anxiety, and repetitive behaviors or mental acts (compulsions) performed to alleviate this distress. Despite affecting approximately 2-3% of the global population (Ruscio et al., 2010; NIMH, 2023), OCD remains one of the most misunderstood and frequently misdiagnosed mental health conditions.

The complexity of OCD stems from its heterogeneous presentation and high comorbidity rates with conditions such as trauma, Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), and autism. Individuals with OCD often experience significant delays between symptom onset and accurate diagnosis, with many receiving inappropriate treatments that may exacerbate their condition. These challenges underscore the critical importance of specialized care in effectively addressing OCD.

This paper aims to provide primary care physicians and frontline medical workers with essential information about OCD, its diagnosis challenges, and the compelling benefits of working with an OCD specialist. By understanding the nuances of OCD and the value of specialized treatment, healthcare providers can significantly improve outcomes for their patients struggling with this difficult condition.

Outcome Measures

Quantitative Assessment Tools for OCD

Accurate assessment of OCD symptoms and treatment progress relies on validated measurement instruments. The most widely recognized and utilized tool is the Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS), often referred to as the "gold standard" for OCD assessment (Goodman et al., 1989a, 1989b).

The Y-BOCS is a structured questionnaire designed to measure the severity of obsessive-compulsive symptoms across two primary components: a symptom checklist and a severity scale. The symptom checklist identifies specific obsessions (e.g., contamination fears, intrusive thoughts) and compulsions (e.g., excessive cleaning, checking behaviors) experienced by the patient. The severity scale then evaluates their intensity and impact on daily functioning using a scoring system from 0 to 4 for each item, with higher scores indicating greater symptom severity (Storch et al., 2010).

The total Y-BOCS score ranges from 0 to 40 and provides clinicians with a standardized measure of symptom severity:

0-7: Subclinical symptoms

8-15: Mild OCD

16-23: Moderate OCD

24-31: Severe OCD

32-40: Extreme OCD

In clinical settings, meaningful improvement is typically defined as a reduction in Y-BOCS scores by specific percentage thresholds. Research has established that reductions of 25% represent mild to moderate improvement, while decreases of 35-50% indicate moderate to marked improvement (Tolin et al., 2005). Controlled treatment trials generally recognize a reduction of 35% or greater as the threshold for a clinically meaningful response.

An updated version, the Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale, Second Edition (Y-BOCS-II), has been developed to more comprehensively evaluate symptom severity, particularly in extremely ill patients, and improve consistency in assessing avoidance behaviors (Storch et al., 2010). The Y-BOCS-II has demonstrated strong internal consistency (α = .90) and convergent validity with other measures of OCD symptoms (Wu et al., 2016).

Other assessment instruments that may be used as complementary measures include:

The Obsessive-Compulsive Inventory-Revised (OCI-R)

The Brown Assessment of Beliefs Scale (BABS)

The Overvalued Ideas Scale (OVIS)

The Dimensional Obsessive-Compulsive Scale (DOCS)

These quantitative measures provide essential data for both initial assessment and ongoing treatment evaluation, allowing clinicians to track patient progress objectively and adjust treatment plans accordingly.

Quantitative Evidence of Treatment Effectiveness

Evidence-based treatments for OCD, particularly when delivered by specialists, have demonstrated significant quantitative improvements in patient outcomes. Multiple studies have shown that specialized OCD treatment using Exposure and Response Prevention (ERP) and Inference-based Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (I-CBT) leads to substantial symptom reduction.

Research indicates that properly administered ERP by OCD specialists typically results in a 50-80% reduction in OCD symptoms for most patients (Foa et al., 2005). This is quantifiably superior to outcomes observed with non-specialized treatments or generalist approaches. A large meta-analysis of cognitive behavioral therapy with ERP for OCD found a large effect size (g = 1.13, 95% CI 0.71 to 1.55) when compared to psychological placebo conditions (Reid et al., 2021). This demonstrates the substantial benefit of specialized treatment over non-specific interventions.

For I-CBT specifically, recent clinical trials have shown it to be particularly effective for certain OCD subtypes, especially those characterized by overvalued ideation. A multicenter randomized controlled trial found that I-CBT produced substantial reductions in OCD symptom severity and demonstrated superior outcomes in addressing overvalued ideation, along with higher remission rates when compared to mindfulness-based stress reduction approaches (Aardema et al., 2022).

These quantitative outcomes underscore the value of specialized care in achieving meaningful symptom reduction and improved quality of life for individuals with OCD.

The Challenge of Diagnosis and Treatment

Research Evidence on Diagnostic Difficulties

The path to accurate OCD diagnosis is fraught with challenges, leading to significant delays in appropriate treatment and unnecessary suffering. Research has consistently documented these difficulties and their impact on patient outcomes.

Delayed Diagnosis

Studies reveal a striking gap between symptom onset and proper diagnosis. According to research published in Comprehensive Psychiatry, people with OCD experience symptoms for an average of 7.1 years before receiving an accurate diagnosis (Hezel et al., 2022). This delay is even more pronounced in older individuals, suggesting a generational gap in OCD recognition.

Another study found an even longer delay, with individuals with OCD living with their symptoms for nearly 11 years before receiving an accurate diagnosis (García-Soriano et al., 2014). This extended period without proper treatment allows the condition to become more entrenched, often leading to functional impairment across multiple life domains.

Misdiagnosis

Misdiagnosis represents a particularly troubling aspect of the OCD diagnostic landscape. Research has demonstrated that approximately 50.5% of OCD cases presented to primary care physicians are misidentified (Glazier et al., 2015). This alarming rate of misdiagnosis varies significantly depending on the specific OCD presentation:

Homosexuality-themed OCD; 84.6% misdiagnosis rate

Aggression-themed OCD; 80.0% misdiagnosis rate

Fear of saying certain things; 73.9% misdiagnosis rate

Pedophilia-themed OCD; 70.8% misdiagnosis rate

Somatic concerns; 40.0% misdiagnosis rate

Religious obsessions; 37.5% misdiagnosis rate

Contamination fears; 32.3% misdiagnosis rate

Symmetry concerns; 3.7% misdiagnosis rate

These findings reveal that OCD presentations that deviate from stereotypical contamination or symmetry concerns are particularly vulnerable to misdiagnosis. This is especially concerning given that "taboo" obsessions (e.g., sexual, aggressive, or religious themes) are common in OCD but frequently misidentified as indicative of other conditions (Williams et al., 2017).

The consequences of misdiagnosis extend beyond delayed treatment. Patients who receive incorrect diagnoses are often subjected to inappropriate interventions that may exacerbate their condition. For instance, individuals misdiagnosed with psychotic disorders may be prescribed antipsychotic medications, which do not address the underlying OCD and can cause significant side effects (Poyraz et al., 2015).

Symptom Heterogeneity

OCD's diverse symptom presentation contributes significantly to diagnostic challenges. While popular media often portrays OCD as characterized by contamination fears or symmetry concerns as above, the condition encompasses a wide range of themes, including:

Harm (fear of harming self or others)

Sexual obsessions

Religious/moral concerns (scrupulosity)

Relationship-centered obsessions

Health-related fears

"Just right" feelings

Need for certainty

This heterogeneity makes OCD difficult to recognize, particularly when symptoms don't align with common stereotypes. Many healthcare providers have limited exposure to the full spectrum of OCD presentations during their training, contributing to misidentification.

Comorbidities

The diagnostic picture is further complicated by OCD's high comorbidity with other conditions. Research indicates substantial overlap between OCD and several neurodevelopmental and psychiatric disorders:

Autism; Studies have identified significant symptom overlap and comorbidity between autism and OCD, with challenges in differentiating restricted, repetitive behaviors in autism from compulsions in OCD (Postorino et al., 2017).

ADHD; Research has found comorbidity rates of approximately 30% between OCD and ADHD, with each condition potentially masking or exacerbating symptoms of the other (Abramovitch et al., 2015).

Trauma; Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and trauma-related disorders have shown significant comorbidity with OCD. Research suggests trauma can both trigger and exacerbate OCD symptoms, while trauma history may influence symptom presentation and treatment response. Studies have found that individuals with OCD report higher rates of traumatic life events compared to the general population, and trauma-informed approaches may be necessary for effective treatment (Mathews et al., 2008; Miller & Brock, 2017).

Anxiety Disorders; Generalized anxiety disorder, social anxiety disorder, and specific phobias frequently co-occur with OCD, creating complex symptom presentations (Brady et al., 2022).

Tic Disorders; Studies report elevated rates of OCD in individuals with tic disorders like Tourette's syndrome, suggesting shared neurobiological mechanisms (Hirschtritt et al., 2018).

Depression; Research indicates that depressive disorders in individuals with OCD are five times higher than in the general population (Torres et al., 2016).

The presence of these comorbidities not only complicates diagnosis but also necessitates specialized knowledge to determine appropriate treatment priorities and approaches.

Specialist vs. Generalist Approach

The complex nature of OCD diagnosis and treatment underscores the importance of specialized expertise. OCD specialists possess distinct advantages over generalists in several key areas:

Superior Symptom Identification

OCD specialists have extensive training and experience in recognizing the diverse presentations of obsessive-compulsive symptoms. Unlike generalists, who may have encountered only a limited range of OCD cases, specialists are familiar with the full spectrum of OCD manifestations.

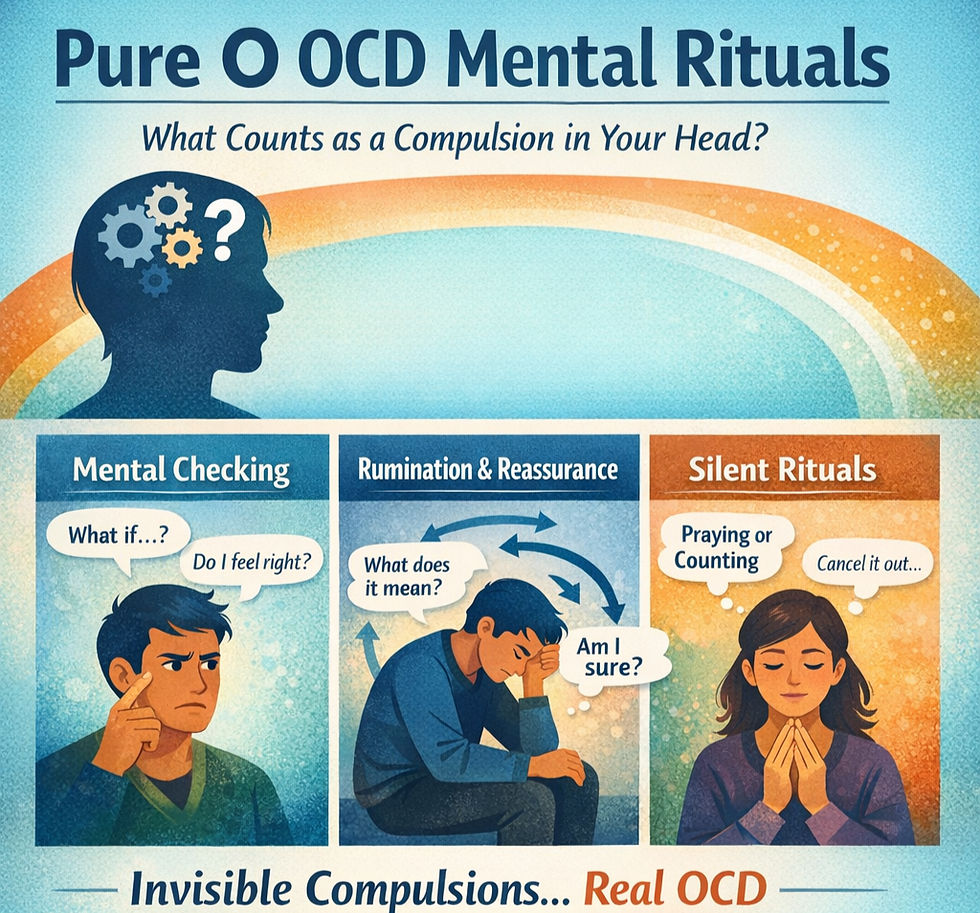

This expertise allows specialists to identify subtle OCD symptoms that might be overlooked by generalists. For example, "Pure O" OCD, characterized by obsessions without visible compulsions, is frequently missed by providers without specialized training. Specialists recognize that these individuals engage in mental compulsions (e.g., mental reviewing, reassurance-seeking) that may not be immediately apparent.

Specialists are also adept at distinguishing between OCD and conditions with overlapping symptoms. For instance, they can differentiate between the intrusive thoughts of OCD and the delusions of psychotic disorders - a distinction that has crucial treatment implications.

Targeted Treatment Structures

OCD specialists employ evidence-based treatment protocols specifically designed for OCD. While generalists may have broad familiarity with cognitive-behavioral approaches, specialists have in-depth training in the specific techniques most effective for OCD.

Specialized treatment for OCD typically involves:

Precise assessment and case conceptualization: Specialists conduct thorough evaluations to identify specific obsessions, compulsions, avoidance behaviors, and maintaining factors.

Tailored exposure hierarchies (for ERP): Specialists create personalized exposure plans that target each patient's unique symptom presentation.

Effective response prevention strategies: Specialists develop strategies to help patients resist compulsions and manage distress, an essential component of successful treatment.

Expertise in addressing treatment obstacles: Specialists anticipate and effectively manage common barriers to OCD treatment, such as accommodation by family members or covert compulsions.

Research supports the superior outcomes achieved by specialists. One study found that patients who received treatment from OCD specialists were significantly more likely to receive first-line empirically supported treatments (CBT = 66.0%, SSRI = 35.0%) compared to those treated by non-specialists (CBT = 46.7%, SSRI = 8.6%) (Glazier et al., 2015).

Management of Comorbidities

The complex interplay between OCD and its common comorbidities requires specialized knowledge. OCD specialists are equipped to:

Identify when symptoms are attributable to OCD versus comorbid conditions: For example, distinguishing between ADHD-related inattention and OCD-related preoccupation with intrusive thoughts.

Determine appropriate treatment sequencing: Understanding which condition to prioritize in treatment when multiple diagnoses are present.

Modify treatment approaches to accommodate comorbidities: Adjusting treatment protocols to accommodate neurodivergence, for instance.

Coordinate care with other specialists when needed: Collaborating effectively with providers treating comorbid conditions.

Examples of Missed or Misplaced Symptoms

Several examples illustrate how OCD symptoms may be misidentified by non-specialists:

Sexual obsessions; Intrusive, unwanted sexual thoughts are common in OCD but may be misinterpreted as indicative of paraphilic disorders or repressed desires. Research shows these presentations are misdiagnosed nearly 85% of the time by primary care physicians (Glazier et al., 2015).

Harm obsessions; Fears of harming others (e.g., stabbing a loved one) may be misinterpreted as homicidal ideation or psychosis rather than recognized as ego-dystonic OCD symptoms.

Relationship OCD; Persistent doubts about one's relationship may be misattributed to relationship problems rather than identified as a manifestation of OCD.

Health anxiety; Obsessions about having or contracting serious illnesses may be diagnosed simply as hypochondriasis without recognition of the underlying OCD mechanisms.

Scrupulosity; Religious or moral obsessions may be viewed as appropriate religious devotion rather than recognized as sources of significant distress and impairment.

These examples highlight the critical importance of specialized knowledge in accurately identifying and addressing the diverse manifestations of OCD. By referring patients to OCD specialists, primary care physicians can ensure that these subtle presentations are not missed or misinterpreted, leading to more timely and effective intervention.

Evidence-based Therapeutic Approaches

Exposure Response Prevention (ERP)

Definition and Mechanism of Action

Exposure and Response Prevention (ERP) is a specialized form of cognitive-behavioral therapy that stands as the original standard psychological treatment for Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. Developed in the 1960s, ERP has amassed decades of research supporting its efficacy and effectiveness.

ERP consists of two core components:

Exposure; Systematically confronting thoughts, images, objects, and situations that trigger obsessions and anxiety

Response Prevention; Making the choice not to engage in compulsive behaviors once anxiety or obsessions have been triggered

The theoretical foundation of ERP lies in basic learning principles. When individuals with OCD encounter anxiety-provoking stimuli, they typically engage in compulsive behaviors to reduce their distress. This temporary relief reinforces both the fear response and the compulsive behavior, creating a self-perpetuating cycle.

ERP breaks this cycle by allowing patients to experience that:

Anxiety naturally decreases over time without compulsions (habituation)

Feared outcomes rarely occur, and when they do, they are typically manageable

Uncertainty can be tolerated without resorting to compulsive behaviors

ERP works by "retraining your brain" to no longer perceive the object of obsession as a threat. The treatment helps patients recognize that their internal alarm system (anxiety) is providing false signals of danger (Abramowitz et al. 2011).

Applications and Examples

ERP can be effectively applied to all subtypes of OCD, though the specific implementation varies based on symptom presentation:

Contamination OCD:

Exposure; Touching "contaminated" surfaces (doorknobs, public restrooms, floors)

Response Prevention; Refraining from hand washing, sanitizing, or seeking reassurance

Checking OCD:

Exposure; Leaving the house without checking locks/appliances multiple times

Response Prevention; Tolerating uncertainty about whether doors are locked or appliances are turned off

Harm OCD:

Exposure; Holding a knife near a loved one (with supervision) or writing out feared scenarios

Response Prevention; Not seeking reassurance that one isn't a dangerous person

Religious/Scrupulosity OCD:

Exposure; Intentionally having "blasphemous" thoughts or engaging in acts perceived as sacrilegious

Response Prevention; Not praying for forgiveness or confessing

Relationship OCD:

Exposure; Spending time with people other than one's partner

Response Prevention; Not comparing feelings or seeking reassurance about the relationship

ERP is typically delivered in a graduated manner, starting with moderately difficult exposures and progressing to more challenging ones as the patient builds confidence and skills. Exposures can be conducted in-vivo (real-life), in-imagination, or interoceptively (focusing on physical sensations).

Quantitative Outcomes

The efficacy of ERP for OCD is supported by robust empirical evidence. Meta-analyses have found a large effect size for cognitive behavioral therapy with ERP in reducing OCD symptoms when compared to psychological placebo conditions (g = 1.13, 95% CI 0.71 to 1.55) (Reid et al., 2021).

Clinical trials consistently demonstrate that:

50-70% of OCD patients show significant improvement with ERP

Treatment gains are typically maintained at follow-up assessments

ERP is effective across the lifespan, benefiting children, adolescents, adults, and older adults

When delivered by specialists, ERP shows superior outcomes compared to medication alone. While Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs) are effective for many patients, research indicates that approximately 45-89% of patients treated with SSRIs alone experience a recurrence of OCD symptoms after medication discontinuation. In contrast, improvements from ERP tend to persist long-term (Pinciotti et al., 2022).

For patients with severe OCD symptoms, intensive ERP formats (daily sessions over several weeks) have been shown to produce rapid and substantial symptom reduction. A 2011 study found that intensive ERP delivered via telehealth was as effective as in-person treatment, with patients maintaining gains at follow-up (Storch et al., 2011).

Inference-based Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (I-CBT)

Definition and Mechanism of Action

Inference-based Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (I-CBT) is a specialized form of cognitive therapy developed specifically for treating Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. Unlike traditional cognitive approaches that focus on challenging the meaning or importance of intrusive thoughts, I-CBT targets the reasoning processes that give rise to obsessional doubts in the first place.

I-CBT is founded on the premise that obsessions are not random intrusive thoughts but are instead doubts that arise from a specific reasoning process characterized by:

Inferential confusion: The tendency to confuse an imagined possibility for a real possibility that needs to be acted upon, despite a lack of sensory evidence in the present moment

Distrust of the senses: Doubting what one sees, hears, or feels in favor of remote possibilities generated by imagination

Overreliance on imagination: Using imagination rather than direct sensory information to determine what is "real" or possible

I-CBT aims to bring resolution to obsessional doubts by teaching clients that obsessional doubts do not arise in the same way as normal doubts. Normal doubts come about for legitimate reasons, and are relevant to the here-and-now, whereas obsessional doubts never are.

The goal of I-CBT is to help patients recognize when they are crossing from reality into imagination-based reasoning, and to teach them to trust their senses and direct experience rather than remote possibilities. This approach targets the "reasoning narrative" that sustains obsessional doubts, enabling patients to dismiss obsessions at their source rather than managing them after they've already taken hold (O'Connor et al., 2005).

Applications and Examples

I-CBT is particularly valuable for OCD presentations that involve highly imaginative or abstract content, where traditional ERP may be more challenging to implement:

Pure Obsessional OCD ("Pure O"); I-CBT helps patients identify the faulty reasoning processes that transform normal intrusive thoughts into obsessions, without requiring direct exposure to feared scenarios.

OCD with Overvalued Ideas; For patients with limited insight or strong conviction in their obsessional beliefs, I-CBT addresses the reasoning patterns that maintain these beliefs, potentially offering better engagement than ERP.

Existential or Philosophical Obsessions; I-CBT can effectively address obsessions about reality, existence, or metaphysical concerns by helping patients recognize when they've shifted from practical reasoning to abstract possibilities.

Sexual, Religious, or Aggressive Obsessions; I-CBT provides a framework for understanding how imagination creates scenarios that feel threatening despite contradicting a person's values and sensory evidence.

A typical I-CBT session might involve:

Mapping the patient's "obsessional sequence" to identify where reasoning crosses from reality to possibility

Analyzing how the imagination generates doubt despite contrary sensory evidence

Practicing "reality-based reasoning" in situations that typically trigger obsessions

Developing awareness of one's vulnerable self-themes that make certain obsessional content particularly sticky

Importantly, I-CBT does not include deliberate exposure exercises or anxiety provocation. Instead, it focuses on cognitive exercises that help patients discriminate between reality-based and imagination-based reasoning. This can make I-CBT a more effective and gentle alternative to ERP for abstract or high-distress symptoms.

Quantitative Outcomes

As a newer modality, I-CBT has a smaller research base than ERP, but evidence for its efficacy is conclusive and growing. According to Julien et al. (2016), studies have "provided support for the theory informing I-CBT and the efficacy of I-CBT as a treatment for OCD."

Specific research findings include:

A multicenter randomized controlled trial found I-CBT led to significant decreases in OCD symptoms following intervention and "greater improvements in overvalued ideation... and increased rates of remission compared to Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction intervention" (Aardema et al., 2022).

Research comparing I-CBT to standard CBT found that I-CBT resulted in higher treatment acceptability scores, suggesting better patient engagement and satisfaction (Visser et al., 2015).

A randomized controlled non-inferiority trial comparing I-CBT to CBT with ERP found that both treatments produced statistically significant improvements in OCD symptoms, with I-CBT demonstrating better tolerability (Aardema et al., 2023).

I-CBT appears particularly beneficial for certain OCD subgroups:

Patients with strong conviction in their obsessional beliefs

Those who have not responded adequately to ERP

Individuals with predominantly mental compulsions

Patients who find exposure-based approaches too distressing or challenging to engage with

The development and validation of I-CBT represent an important advance in OCD treatment, providing an alternative evidence-based approach for patients who may not benefit optimally from ERP alone. The availability of multiple effective treatment options underscores the value of specialist care, as specialists can select and implement the approach most suited to each patient's unique presentation.

Removing Barriers to OCD Care

Identifying Barriers to Care

Despite the availability of effective treatments, many individuals with OCD face significant obstacles in accessing appropriate care. These barriers exist at multiple levels - healthcare system, provider, and patient - and collectively contribute to the substantial treatment gap observed in OCD.

Healthcare System Barriers

The structure and organization of healthcare systems frequently impede access to specialized OCD treatment:

Limited availability of specialists; There is a severe shortage of clinicians with specialized training in evidence-based OCD treatments, particularly in rural and underserved areas.

Insurance coverage limitations; Many insurance plans offer inadequate coverage for mental health services, impose high deductibles or copayments, or restrict the number of sessions covered.

Long waiting lists; The scarcity of specialists often results in extended waiting periods for initial appointments, during which time symptoms may worsen.

Fragmented care; The separation between primary care and mental health services can create coordination challenges and referral difficulties.

Inadequate training infrastructure; Limited opportunities for clinicians to receive specialized training in OCD treatment perpetuates the shortage of qualified providers.

Research indicates that these systemic barriers contribute significantly to the treatment gap, with as many as 60% of individuals with OCD remaining untreated (Kohn et al., 2004).

Provider Barriers

Healthcare providers themselves may inadvertently create obstacles to effective OCD treatment:

Lack of knowledge about OCD; Many providers receive minimal training in OCD recognition and treatment, leading to missed or delayed diagnoses.

Misdiagnosis; As previously discussed, OCD is frequently misidentified as other conditions, particularly when presentations deviate from stereotypical contamination or symmetry concerns.

Insufficient expertise in evidence-based treatments; Even when correctly diagnosed, patients may not receive first-line treatments (ERP or I-CBT) due to provider unfamiliarity with these approaches.

Underutilization of evidence-based practices; Research has found that despite the established efficacy of ERP, many clinicians do not offer this treatment due to misconceptions or discomfort with its implementation (Pinciotti et al., 2022).

Stigma and misconceptions; Some providers harbor misconceptions about OCD or may inadvertently stigmatize patients, creating barriers to effective communication and treatment.

Studies have documented the impact of these provider barriers. For example, a survey of mental health professionals found significant gaps in knowledge about OCD symptoms and treatment, with many respondents expressing low confidence in their ability to effectively treat the condition (Glazier et al., 2013).

Patient Barriers

Individuals with OCD face numerous personal barriers to seeking and engaging in treatment:

Stigma and shame; Many OCD themes (e.g., sexual, aggressive, or religious obsessions) are associated with intense shame, making disclosure difficult.

Lack of awareness; Patients may not recognize their symptoms as OCD, particularly when they don't align with popular portrayals of the disorder.

Fear of treatment; The prospect of ERP, which involves confronting feared stimuli, can be intimidating and may deter treatment-seeking.

Logistical challenges; Transportation issues, work or family responsibilities, and geographic distance from providers create practical obstacles.

Financial constraints; Out-of-pocket costs for specialized treatment may be prohibitive for many individuals.

Research shows that approximately 30% of adults with OCD did not initiate recommended CBT treatment or dropped out prematurely, with logistical issues, financial concerns, and lack of time commonly reported as obstacles (Mancebo et al., 2011).

The combination of these multi-level barriers creates a significant impediment to effective OCD treatment, resulting in unnecessary suffering and functional impairment for affected individuals.

Solutions to Address Barriers

Addressing the complex barriers to OCD care requires a multifaceted approach that targets healthcare systems, providers, and patients. Several promising solutions have emerged:

Telehealth as an Accessibility Tool

Telehealth has revolutionized access to specialized OCD treatment, particularly for individuals who face geographic or mobility limitations. Research supports the efficacy of telehealth-delivered OCD treatment:

A study published in the Journal of Medical Internet Research found that video teletherapy for OCD produced a 43.4% mean reduction in obsessive-compulsive symptoms with a large effect size (g=1.0) and a 62.9% response rate (Feusner et al., 2022).

Research has demonstrated that intensive ERP delivered via telehealth was as effective as in-person treatment for OCD (Storch et al., 2011).

A retrospective study of telehealth-delivered ERP during the COVID-19 pandemic found that both virtual and in-person modalities were effective at treating OCD symptoms, though the telehealth group required slightly longer treatment duration (Sequeira et al., 2022).

Telehealth offers several specific advantages for OCD treatment:

Geographic reach; Patients can access specialists regardless of their location, eliminating travel barriers.

In-context treatment; Therapists can observe and address OCD symptoms in the patient's natural environment, where they actually occur.

Time efficiency; Elimination of travel time increases treatment adherence and reduces missed appointments.

Cost-effectiveness; Research indicates that telehealth treatment achieves comparable results in less than half the total therapist time compared to standard weekly outpatient treatment (Feusner et al., 2022), representing substantial cost savings.

Privacy; Receiving treatment from home may reduce stigma concerns for some patients.

The growing evidence base for telehealth-delivered OCD treatment represents a significant advance in addressing accessibility barriers, particularly for underserved populations.

Improving Physician Recognition and Referral

Primary care physicians and other frontline healthcare providers play a crucial role in identifying potential OCD and facilitating appropriate referrals. Several strategies can enhance their effectiveness in this regard:

Enhanced education and training; Brief educational interventions focusing on recognizing diverse OCD presentations can significantly improve diagnostic accuracy among primary care providers.

Implementation of screening tools; Incorporating validated screening measures (e.g., the Obsessive-Compulsive Inventory-Revised) into primary care settings can help identify patients who may benefit from specialist evaluation.

Development of clear referral pathways; Establishing streamlined referral processes between primary care and OCD specialists reduces delays in accessing appropriate care.

Regular consultation with specialists; Collaborative care models that facilitate ongoing communication between primary care providers and mental health specialists improve patient outcomes.

Resources for patient education; Equipping primary care providers with accurate, accessible information about OCD helps patients better understand their symptoms and treatment options.

Research indicates that improvements in physician recognition and referral practices can significantly reduce the delay between symptom onset and appropriate treatment, leading to better long-term outcomes.

Collaborative Care Models

Effective collaboration between primary care physicians and OCD specialists ensures comprehensive, coordinated care for patients:

Shared decision-making; Primary care physicians and specialists can work together with patients to develop treatment plans that address both OCD and any co-occurring medical conditions.

Ongoing communication; Regular updates between providers facilitate monitoring of medication effects, symptom changes, and treatment progress.

Coordinated care transitions; Thoughtful planning for transitions between levels of care (e.g., from intensive treatment to maintenance) helps sustain treatment gains.

Integration of physical and mental health; Addressing both psychological and physical health needs improves overall patient well-being.

Family involvement; With appropriate patient consent, including family members in the collaborative care process enhances treatment support and reduces accommodation of symptoms.

Collaborative care models have been shown to improve treatment adherence, patient satisfaction, and clinical outcomes across a range of mental health conditions, including OCD.

Economic Considerations and Cost-Effectiveness

The economic case for specialized OCD care provides compelling support for specialist intervention as a healthcare priority. Research demonstrates that although specialized OCD treatment may have higher initial costs, it yields superior cost-effectiveness over the long term through several mechanisms.

Cost-effectiveness analyses demonstrate that specialized interventions, while requiring more resources upfront, typically result in fewer relapses and hospitalizations, ultimately reducing long-term healthcare expenditures (Storch et al., 2011). This economic benefit is particularly significant given the chronic nature of OCD when inadequately treated.

Delayed or incorrect treatment carries substantial economic consequences. Multiple studies confirm that untreated or mismanaged OCD generates significant indirect costs, including lost productivity, employment difficulties, and increased utilization of healthcare services. Researchers have found that individuals with untreated OCD experience substantial functional impairment across occupational, academic, and social domains, translating to considerable societal costs that could be mitigated through appropriate specialist care (Torres et al., 2016).

Misdiagnosis creates additional financial burdens beyond direct treatment costs. When patients receive incorrect diagnoses such as psychotic disorders, they often undergo treatment with inappropriate medications that carry significant side effects. This frequently leads to cascading healthcare costs including additional medical visits, medication changes, and management of iatrogenic symptoms, creating a cycle of inappropriate care and economic inefficiency (Poyraz et al., 2015).

Comprehensive economic evaluations of OCD treatment should include:

Direct cost comparisons between specialist and generalist approaches, including session fees, medication expenses, and potential inpatient treatment

Quantification of reduced indirect costs resulting from effective specialized treatment, such as improved work productivity and decreased disability claims

Quality-adjusted life year (QALY) analyses comparing outcomes from specialized versus generalist approaches

Long-term economic modeling that accounts for OCD's typically early onset and chronic nature

Early identification and referral to specialists represents sound healthcare economics by preventing the substantial costs associated with prolonged, ineffective treatment approaches. When combined with expanded telehealth services, improved physician recognition and referral practices, and collaborative care models, the healthcare system can significantly reduce barriers to specialized OCD treatment while achieving better economic outcomes. These integrated approaches increase access to care while improving service quality and coordination, ultimately producing better clinical and economic outcomes for individuals affected by OCD.

Conclusion

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder represents a significant challenge for healthcare providers due to its complex and varied presentation, high rates of comorbidity, and the specialized knowledge required for effective treatment. This white paper has outlined the compelling evidence supporting the referral of patients with suspected OCD to specialists rather than generalists.

The research presented demonstrates several key findings:

OCD is frequently misdiagnosed and undertreated. Studies show alarming rates of misdiagnosis, with approximately 50% of OCD cases misidentified by primary care physicians (Glazier et al., 2015). This rate increases dramatically for less stereotypical presentations, such as sexual or harm-themed obsessions, which are misdiagnosed up to 85% of the time.

The consequences of misdiagnosis are severe. Patients who receive incorrect diagnoses often undergo inappropriate treatments, including medications that may exacerbate their condition. The average delay between symptom onset and proper diagnosis - 7 to 13 years according to recent research - represents a significant period of unnecessary suffering and functional impairment.

Specialists achieve superior outcomes. OCD specialists possess the expertise to accurately identify the diverse manifestations of OCD, implement evidence-based treatments with fidelity, and manage complex comorbidities. Quantitative data show that patients treated by specialists are significantly more likely to receive first-line empirically supported treatments and achieve substantial symptom reduction.

Evidence-based treatments are highly effective when properly delivered. Both Exposure and Response Prevention (ERP) and Inference-based Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (I-CBT) have demonstrated robust efficacy in reducing OCD symptoms. Meta-analyses show large effect sizes for these specialized interventions, with treatment gains typically maintained at follow-up.

Telehealth and collaborative care models are expanding access to specialized treatment. Research supports the efficacy of telehealth-delivered OCD treatment, which achieves comparable results to in-person care while reducing barriers related to geography, time, and cost.

For primary care physicians and frontline medical workers, the implications are clear: early recognition of potential OCD symptoms and prompt referral to specialists are essential steps in ensuring optimal patient outcomes. By developing familiarity with the diverse presentations of OCD, implementing brief screening measures, and establishing relationships with OCD specialists, primary care providers can play a crucial role in reducing diagnostic delays and facilitating access to effective treatment.

The evidence presented in this white paper underscores that specialist referral is not merely a matter of preference but a standard of care issue for patients with OCD. Just as complex medical conditions warrant referral to appropriate specialists, the complexity of OCD demands the expertise of clinicians specifically trained in its assessment and treatment.

By prioritizing early referral to OCD specialists, primary care physicians can significantly improve the trajectory of this often-debilitating condition, helping patients reclaim their lives from the grip of obsessions and compulsions. The quantitative data is unequivocal: specialized care for OCD saves time, reduces suffering, and ultimately leads to better outcomes for the millions of individuals affected by this challenging disorder.

References

Aardema, F., Bouchard, S., Koszycki, D., Lavoie, M. E., Audet, J. S., & O'Connor, K. (2022). Evaluation of Inference-Based Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: A Multicenter Randomized Controlled Trial with Three Treatment Modalities. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 91(5), 348-359. https://doi.org/10.1159/000524425

Aardema, F., Wong, S. F., Audet, J. S., Melli, G., & Baraby, L. P. (2023). Inference-Based Cognitive Behavioral Therapy versus Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: A Multisite Randomized Controlled Non-Inferiority Trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 91(4), 312-324. https://doi.org/10.1159/000541508

Abramovitch, A., Dar, R., Mittelman, A., & Wilhelm, S. (2015). Comorbidity between attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder across the lifespan. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 23(4), 245-262. https://doi.org/10.1097/HRP.0000000000000050

Abramowitz, J. S., Deacon, B. J., & Whiteside, S. P. (2011). Exposure therapy for anxiety: Principles and practice. Guilford Press.

Brady, R. E., Cisler, J. M., & Lohr, J. M. (2022). Specific and general anxiety sensitivity in comorbid anxiety and obsessive-compulsive spectrum disorders. Journal of Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders, 33, 100710.

Comer, J. S., Furr, J. M., Kerns, C. E., Miguel, E., Coxe, S., Elkins, R. M., Carpenter, A. L., Cornacchio, D., Cooper-Vince, C. E., DeSerisy, M., Chou, T., Sanchez, A. L., Khanna, M., Franklin, M. E., Garcia, A. M., & Freeman, J. B. (2017). Internet-delivered, family-based treatment for early-onset OCD: A pilot randomized trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 85(2), 178-186. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000155

Deacon, B. J., Farrell, N. R., Kemp, J. J., Dixon, L. J., Sy, J. T., Zhang, A. R., & McGrath, P. B. (2013). Assessing therapist reservations about exposure therapy for anxiety disorders: The Therapist Beliefs about Exposure Scale. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 27(8), 772-780. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2013.04.006

Feusner, J. D., Carpenter, C., Rozenman, M., Rosario, M. C., Katzenstein, T., Rettew, D., Dahan, A., Kang, D., Collins, S. A., Ranek, M., Nadeau, R. D., Zaso, M. J., Garner, L. E., & McGrath, P. (2022). Online Video Teletherapy Treatment of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder Using Exposure and Response Prevention: Clinical Outcomes From a Retrospective Longitudinal Observational Study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 24(5), e36431. https://doi.org/10.2196/36431

Foa, E. B., Liebowitz, M. R., Kozak, M. J., Davies, S., Campeas, R., Franklin, M. E., Huppert, J. D., Kjernisted, K., Rowan, V., Schmidt, A. B., Simpson, H. B., & Tu, X. (2005). Randomized, placebo-controlled trial of exposure and ritual prevention, clomipramine, and their combination in the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry, 162(1), 151-161. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.162.1.151

García-Soriano, G., Rufer, M., Delsignore, A., & Weidt, S. (2014). Factors associated with non-treatment or delayed treatment seeking in OCD sufferers: A review of the literature. Psychiatry Research, 220(1-2), 1-10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2014.07.009

Glazier, K., Calixte, R. M., Rothschild, R., & Pinto, A. (2013). High rates of OCD symptom misidentification by mental health professionals. Annals of Clinical Psychiatry, 25(3), 201-209. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23926575/

Glazier, K., Swing, M., & McGinn, L. K. (2015). Half of obsessive-compulsive disorder cases misdiagnosed: vignette-based survey of primary care physicians. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 76(6), e761-e767. 10.4088/JCP.14m09110

Goodman, W. K., Price, L. H., Rasmussen, S. A., Mazure, C., Delgado, P., Heninger, G. R., & Charney, D. S. (1989a). The Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale. II. Validity. Archives of General Psychiatry, 46(11), 1012-1016. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.1989.01810110054008

Goodman, W. K., Price, L. H., Rasmussen, S. A., Mazure, C., Fleischmann, R. L., Hill, C. L., Heninger, G. R., & Charney, D. S. (1989b). The Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale. I. Development, use, and reliability. Archives of General Psychiatry, 46(11), 1006-1011. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.1989.01810110048007

Hezel, D. M., Rose, S. V., & Simpson, H. B. (2022). Delay to diagnosis in OCD. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 115, 152279. 10.1016/j.jocrd.2022.100709

Hirschtritt, M. E., Darrow, S. M., Illmann, C., Osiecki, L., Grados, M., Sandor, P., Dion, Y., King, R. A., Pauls, D., Budman, C. L., Cath, D. C., Greenberg, E., Lyon, G. J., Scharf, J. M., Hoekstra, P. J., Posthuma, D., & Smit, J. H. (2018). Genetic and phenotypic overlap of specific obsessive-compulsive and attention-deficit/hyperactive subtypes with Tourette syndrome. Psychological Medicine, 48(2), 279-293. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291717001672

ICBTonline. (2024). What is I-CBT? Inference-based Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy. https://icbt.online/what-is-icbt/

Julien, D., O'Connor, K. P., & Aardema, F. (2016). The inference-based approach to obsessive-compulsive disorder: A comprehensive review of its etiological model, treatment efficacy, and model of change. Journal of Affective Disorders, 202, 187-196. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2016.05.060

Kohn, R., Saxena, S., Levav, I., & Saraceno, B. (2004). The treatment gap in mental health care. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 82(11), 858-866. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15640922/

Mancebo, M. C., Eisen, J. L., Sibrava, N. J., Dyck, I. R., & Rasmussen, S. A. (2011). Patient utilization of cognitive-behavioral therapy for OCD. Behavior Therapy, 42(3), 399-412. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2010.10.002

Mathews, C. A., Kaur, N., & Stein, M. B. (2008). Childhood trauma and obsessive-compulsive symptoms. Depression and Anxiety, 25(9), 742-751. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.20316

McCarty, R. J., Guzick, A. G., Swan, L. K., & McNamara, J. P. H. (2022). A systematic review of misdiagnosis in those with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 85, 102510. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jadr.2021.100231

Miller, M. L., & Brock, R. L. (2017). The effect of trauma on the severity of obsessive-compulsive spectrum symptoms: A meta-analysis. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 47, 29-44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2017.02.005

National Institute of Mental Health. (2023). Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD). https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/obsessive-compulsive-disorder-ocd

O'Connor, K., Aardema, F., & Pélissier, M. C. (2005). Beyond reasonable doubt: Reasoning processes in obsessive-compulsive disorder and related disorders. John Wiley & Sons Ltd. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/0470030275

Ong, C. W., Clyde, J. W., Bluett, E. J., Levin, M. E., & Twohig, M. P. (2016). Dropout rates in exposure with response prevention for obsessive-compulsive disorder: What do the data really say? Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 40, 8-17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2016.03.006

Pinciotti, C. M., Bulkes, N. Z., Horvath, G., Riemann, B. C. (2022). Efficacy of intensive CBT telehealth for obsessive-compulsive disorder during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders, 32, 100705. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jocrd.2021.100705

Postorino, V., Kerns, C. M., Vivanti, G., Bradshaw, J., Siracusano, M., & Mazzone, L. (2017). Anxiety disorders and obsessive-compulsive disorder in individuals with autism spectrum disorder. Current Psychiatry Reports, 19(12), 92. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-017-0846-y

Poyraz, C. A., Turan, Ş., Sağlam, N. G., Batun, G. Ç., Yassa, A., & Duran, A. (2015). Factors associated with the duration of untreated illness among patients with obsessive compulsive disorder. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 58, 88-93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2014.12.019

Reid, J. E., Laws, K. R., Drummond, L., Vismara, M., Grancini, B., Mpavaenda, D., & Fineberg, N. A. (2021). Cognitive behavioural therapy with exposure and response prevention in the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 106, 152223. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2021.152223

Ruscio, A. M., Stein, D. J., Chiu, W. T., & Kessler, R. C. (2010). The epidemiology of obsessive-compulsive disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Molecular Psychiatry, 15(1), 53-63. https://doi.org/10.1038/mp.2008.94

Storch, E. A., Larson, M. J., Price, L. H., Rasmussen, S. A., Murphy, T. K., & Goodman, W. K. (2010). Psychometric analysis of the Yale-Brown Obsessive--Compulsive Scale Second Edition Symptom Checklist. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 24(6), 650-656. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2010.04.010

Storch, E. A., Caporino, N. E., Morgan, J. R., Lewin, A. B., Rojas, A., Brauer, L., Larson, M. J., & Murphy, T. K. (2011). Preliminary investigation of web-camera delivered cognitive-behavioral therapy for youth with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Psychiatry Research, 189(3), 407-412. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2011.05.047

Tolin, D. F., Abramowitz, J. S., & Diefenbach, G. J. (2005). Defining response in clinical trials for obsessive-compulsive disorder: A signal detection analysis of the Yale-Brown obsessive compulsive scale. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 66(12), 1549-1557. https://doi.org/10.4088/jcp.v66n1209

Torres, A. R., Ferrão, Y. A., Shavitt, R. G., Diniz, J. B., Costa, D. L., do Rosário, M. C., Miguel, E. C., & Fontenelle, L. F. (2016). Panic disorder and agoraphobia in OCD patients: Clinical profile and possible treatment implications. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 70, 88-94. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2013.11.017

Visser, H. A., van Megen, H., van Oppen, P., Eikelenboom, M., Hoogendorn, A. W., Kaarsemaker, M., & van Balkom, A. J. (2015). Inference-based approach versus cognitive behavioral therapy in the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder with poor insight: A 24-session randomized controlled trial. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 84(5), 284-293. https://doi.org/10.1159/000382131

Williams, M. T., Crozier, M., & Powers, M. (2017). Treatment of sexual-orientation obsessions in obsessive-compulsive disorder using exposure and ritual prevention. Clinical Case Studies, 10(1), 23-36. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534650110393732

Wu, M. S., Bernstein, D., Lavery, J. M., Rudy, B. M., Hsia, J. K., Abraham, K. S., Geller, D. A., & Storch, E. A. (2016). Psychometric properties of the Yale-Brown obsessive-compulsive scale, second edition, self-report (Y-BOCS-II-SR). Comprehensive Psychiatry, 129, 152442. https://doi.org/10.1097/pra.0000000000000823